To Build, or Not to Build? Meeting local authority housing targets and addressing shortfalls

Nine out of Kent’s 13 local authorities are falling short of their five*-year housing delivery targets, with six of them struggling to identify enough land for new homes. LEP Planner Hannah Wilson delves into the complex issues surrounding Local Authority Housing Land Supply targets, the Housing Delivery Test, and the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF). In this report, she examines the factors behind these deficits and explores potential solutions to address the growing undersupply of housing in the region.

By Hannah Wilson

We’ve all heard that we have a housing shortage on our hands in this country but what is the reason for our deficiency of housing? Well, many would argue that the obvious reason is because we are not building enough houses, but that poses the question how do we measure housing delivery and what is the process involved in identifying land suitable for housing? This short piece takes a peek into the processes local planning authorities (LPA) adhere to when it comes to identifying land for housebuilding and meeting housing delivery demand. As well as this, the piece will cover the consequences that might arise if LPAs fail to meet national standards for housing delivery. Obviously, this issue is complex but understanding the way councils address increasing the housing supply is the first step to being able to think about how we can address the issue of the housing shortage.

HLS, NPPF, HDT… what does it all mean?

First, and centrally to this piece, the meaning of Housing Land Supply (HLS) must be tackled. HLS is the identification of a five* year supply of land that can be considered ‘deliverable housing sites’ within a local authority. In this case a ‘deliverable’ housing site may be a site with outline planning permission for residential development or a site on a brownfield land register. The land requirement for the five-year supply will be set out in the LPA’s housing requirement which is usually found amongst their adopted strategic policies. Every district level council is required to identify five* years’ worth of deliverable housing sites in their annual monitoring reports which should be published yearly by the LPA. Where a five* year land supply cannot be met, the presumption in favour of sustainable development (paragraph 11(d) of the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF)) will apply. In terms of decision making, the presumption in favour of sustainable development bolsters the idea that development proposals that align with the development plan should be approved as long as any adverse impacts of approving the development would not ‘significantly and demonstrably’ outweigh any benefits of the proposed development.

How are Kent’s Local Authorities performing?

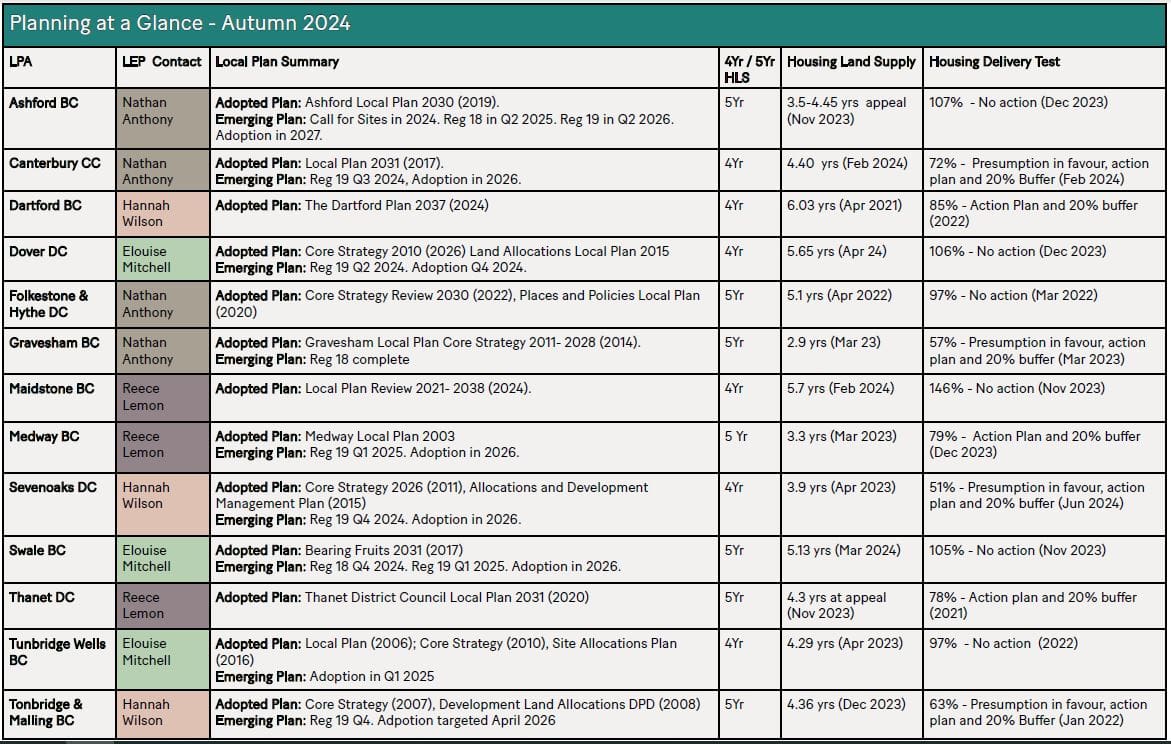

As of the most recent data published on housing land supply, 6 of the 13 Kent local authorities could not identify a 5* year supply of deliverable housing land which raises the question; why are these Kent councils unable to identify sufficient land for housing development? It could be a number of reasons not limited to a poor-quality ‘call for sites’ yield and environmental factors such as the Stodmarsh Nutrient Neutrality Catchment. One consideration that may reduce the deficit of deliverable land is the proposed introduction of the grey belt into the NPPF, but the outcomes from this type of land will only be beneficial to areas with the designation of grey belt land, so understandably not every authority will benefit from this additional land resource.

Realistically, what really matters to the general population in this housing shortage is that houses are actually being delivered, not just the land being identified for housing. Housing Delivery Test (HDT) is a measurement used to calculate the percentage of homes built against the identified requirement in England over a rolling three-year period, which was introduced in 2019. The test is presented as a percentage, with a score of 100% reflecting that the housing delivery target for the local authority has been met. In Kent, the most recent figures show that 9 out of the 13 Kent local authorities were not able to achieve 100% of the housing delivery that would be needed to meet the housing requirements of the area. The under delivery of homes is an issue that has to be tackled so there are some implications that come with this notably a series of actions and consequences depending on the level of under delivery that are shown below.

If the HDT score is:

- 96% and above, no further action should be taken

- 85% – 95%, an action plan that identifies reasons for under delivery and sets out measures to ensure delivery is met should be published within 6 months

- 75% – 85%, an action plan should be published and a 20% buffer should be included to the authority’s current 5* year housing land supply

- 74% and below, an action plan should be published, a 20% buffer should be added to the current housing land supply and the presumption in favour of sustainable development applies which has been defined earlier in the post.

Measures are therefore in place to improve housing delivery when councils fail to deliver however, despite these measures being in place many councils still struggle to meet the housing delivery targets set, and in the new consultation of the NPPF, for many councils housing targets are set to rise. Housing under delivery is affected by many factors and frequently it comes down to good planning, communication with the local council and quality construction to get developments over the line in good time.

Below, we have summarised the performance of Kent’s 13 Local Authorities, which will form the basis of our ongoing series ‘Planning at a Glance’ (keep tuned for regular updates!):

(If you have any queries about the table above, or would like to speak to one of our team, your LEP contact point is outlined in the table under ‘LEP Contact’ – please do reach out.)

How can we improve the situation?

So, with all the presented information what can be done to improve the housing land supply and delivery of housing? The pressure here is on councils to identify more suitable land for housebuilding and to work with applicants to approve residential development applications. However, one solution to this issue that applies to landowners wanting to develop their land, is to reach out to a planning consultant such as the consultants in our planning team at Lee Evans (shown above) who can vouch for the land to be considered as an allocated housing site in revised versions of the local plan. Having an allocated site for housing in the local plan makes it much easier to gain planning permission on this land and ultimately, there will be less chance of refusal from the LPA.

Communication between planning consultants and LPA teams plays an important role in bringing about opportunities for new housing development, particularly when it comes to the curation of new local and land allocation plans. Although this communication may not solve housing deficits, stronger relationships and communication serve to maintain a healthier environment for the approval of planning applications regarding housing developments. What will be interesting to watch out for is how the NPPF consultation will (or will not) alter the way the housing process is governed and the effects that it will have on housing delivery.

*Some councils will only be required to demonstrate a 4-year housing land supply under the current NPPF guidance.

Contact the Team:

If you’d like to discuss this topic further with our planning team, you can contact them at planning@lee-evans.co.uk.

Don’t forget, as well as Kent, we cover the whole of the South East, London, and further afield – so drop our team a line.